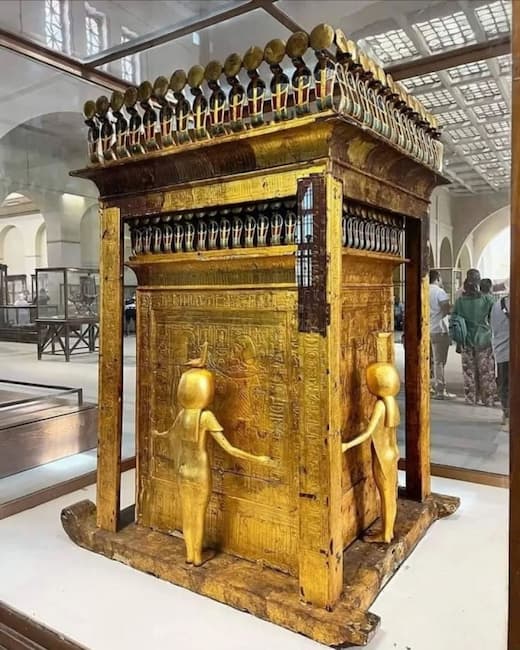

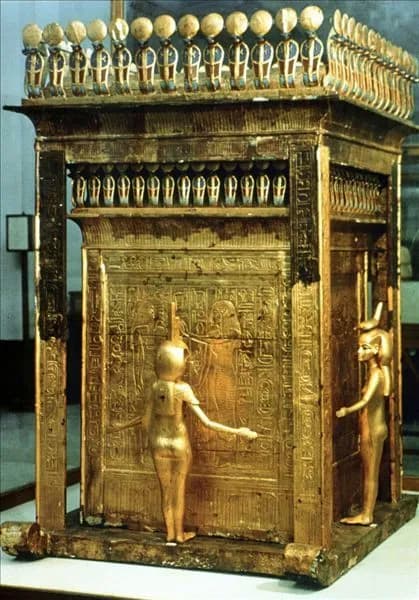

Amidst the grandeur of an intricately adorned canopic shrine lay the enigmatic alabaster chest housing four diminutive coffins. Stand at the side of this opulent shrine, and you’ll encounter statues of four female deities—Isis, Nephthys, Neith, and Serket—each with a countenance subtly turned and arms outstretched in a protective stance.

The outer veneer, a gilded wooden canopy affixed to a sledge, features four corner posts supporting a jutting cavetto cornice crowned by a frieze adorned with uraei, those rearing cobras accompanied by solar disks. This cavetto cornice, a molding with a cross section akin to a quarter circle, encapsulates the essence of ornate complexity. Scenes of safeguarding divinities are etched in relief on the shrine’s sides, adding another layer of bewilderment to the already elaborate tableau.

Behold the Canopic Shrine of King Tutankhamun, where a gilded wooden effigy of the goddess Serket extends her arms protectively, crowned with a scorpion—an unmistakable identifier. Within this shrine rested a calcite chest cradling jars containing the monarch’s vital organs.

Delve into the medical practices of ancient Egypt, a realm where an advanced understanding of maladies coexisted with the healing virtues of massages, aromas, and specialized male and female physicians. Magic seamlessly intertwined with medicine, as practitioners uttered incantations aligning themselves with deities to augment the potency of treatments.

Enter the mystical realm of goddess Serket, often depicted with a scorpion adorning her crown, invoked to remedy the venomous bites of creatures. Her full name, “Serket hetyt,” translates to “she who makes the throat breathe,” alluding to the scorpion’s perilous nature and the goddess’s dual role as a healer and a harbinger of destruction.

Canopic chests, vessels employed by ancient Egyptians in the mummification process, sheltered extracted internal organs—liver, intestines, lungs, and stomach. Noticeably absent was a jar for the heart, revered as the soul’s abode and left intact within the body. These jars, guardians of the departed’s essential parts, accompanied them on the journey to the Afterlife.

From the depths of Tutankhamun’s tomb in the Valley of the Kings, this enigmatic narrative unfolds, now housed in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. JE 60686 bears witness to the perplexing amalgamation of ancient beliefs and practices, inviting contemplation on the intricacies of life, death, and the mystical passage beyond.