One such weapon is the bronze khopesh, a sickle-shaped sword, usually described as a kind of sword-ax, widely used among warriors in the ancient Near East from 3000 BC to about 1300 BC.

The khopesh is mainly known from Egypt and, for the first time, is in the sources of the XVII dynasty as the weapon of Pharaoh Kamose, the last king of the 17th dynasty (c. 1630–1540 BC). In manufacturing this weapon, the Egyptians learned from the Canaanites or took it directly from the invading Hyksos, along with other military innovations.

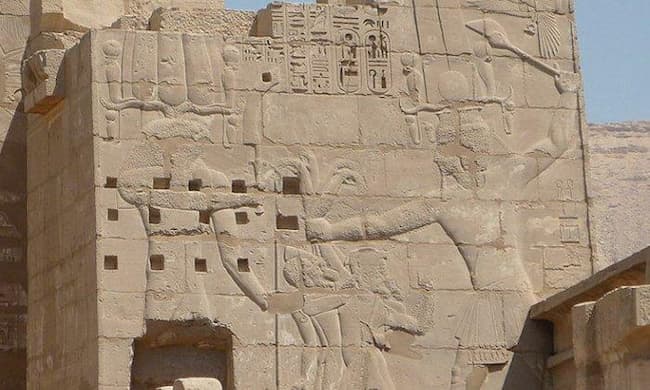

In many depictions, the khopesh represents an emblem of the Egyptian deities and a symbolic weapon of the Pharaohs. Some khopesh were discovered in royal graves, such as the two examples found with Tutankhamun.

In her book “Warfare and Weaponry of Dynastic Egypt,” Rebecca Dean writes that “while the ax remained an important weapon throughout the Eighteenth Dynasty, it at times appeared to be gradually replaced with the sickle sword – the khopesh.”

The author describes the weapon’s blade as “wedge-shaped (widening at the back) with the cutting edge on the outer edge, as in the case of the scimitar blade, and functioned as a long and thin, almost ax-like weapon. Typically, the weapon is 50-60 cm (20–24 inches) long, but also smaller specimens are found. Its sharpness concentrates only on the outside portion of the curved end.” 2

Technically, the khopesh is distinguished from other weapons by its considerable penetration. Its weight was approximately two kilograms, and the unique shape allowed the warrior to choose the way to attack in different conditions.

The khopesh evolved from the epsilon or similar crescent-shaped axes used in warfare.

Dan Howard writes in his book “Bronze Age Military Equipment” that “the khopesh shows” the probable evolution from the epsilon ax (not the sickle). The epsilon ax was likely the ancestor of the khopesh. Cutting typologies were more common in Egypt, but they also used piercing axes.” 3

The khopesh’s blade’s blunt end edge effectively served as a stick and hook. The inside curve was used to trap an opponent’s arm or pull his shield out of the way.

The handle is separated from the barrel by a slight thickening, which forms a barrier directly protecting the hand from a blow. A straight handle with an extended or bent head helps to strengthen the grip.

These weapons changed from bronze to iron in the New Kingdom period between the 16th century BC and the 11th century BC, covering Egypt’s Eighteenth, Nineteenth, and Twentieth dynasties.

In ancient Egypt, the word khopesh (perhaps derived from “leg” (“leg of beef”) because of their similarity in shape. The hieroglyph for hps (‘leg’ or (kh.p.sh = ‘knee’) is found as early as the Coffin Texts (c. 2181–2055 BC).

Many weapon smiths worked hard for a very long time to produce a long sword that was both resilient and capable of taking a hard edge so that it could be used effectively for striking and thrusting. One solution was the bronze khopesh that “despite its odd shape, was widely used in the Middle East, and subsequently evolved into such swords as the Greek “machaira” and the Ghurka “kukri,” traditionally associated with the Nepali-speaking Gurkhas of Nepal and India. 2

The earliest known depiction of a khopesh is from the Stele of Vultures, showing King Eannatum of Lagash with the khopesh in his hand; this would date the khopesh to at least 2500 BC. There are other depictions of the khopesh, too.

One of the earliest is on a Mari cylinder seal. At Byblos and Shechem, a Canaanite city mentioned in the Amarna letters and the Hebrew Bible’s first capital of the Kingdom of Israel dated to a century later.

Except for battles, the khopesh also represented one of the emblems associated with the most important deities of ancient Egypt and symbolized the magical weapon of the Pharaoh.