Will the East African Rift divide the continent and give rise to a novel ocean, or will its energy dissipate?

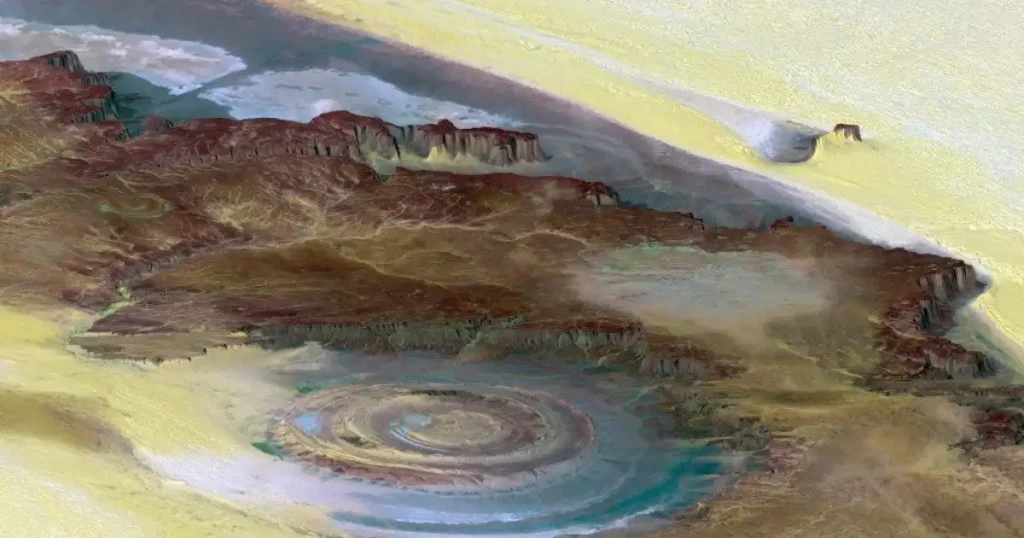

An aerial perspective reveals the East African Rift, featuring a river flowing through a cultivated valley flanked by steep cliffs.

A colossal chasm is gradually rending Africa, the second-largest continent, asunder. This geological depression, recognized as the East African Rift, forms an interconnected network of valleys spanning approximately 2,175 miles (3,500 kilometers) from the Red Sea to Mozambique, as reported by the Geological Society of London.

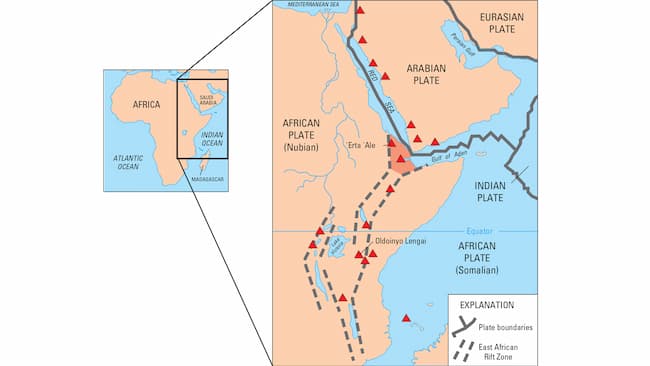

So, will Africa experience a complete rupture, and if so, when shall it occur? To address this inquiry, let us examine the tectonic plates present in the region—outer segments of the planet’s surface that can either converge, generating towering mountains, or diverge, creating expansive basins.

Within this tremendous rift in eastern Africa, the Somalian tectonic plate propels itself eastward away from the larger, more ancient portion of the continent, namely the Nubian tectonic plate, as documented by NASA’s Earth Observatory. (The Somalian plate is also commonly referred to as the Somali plate, while the Nubian plate is sometimes denoted as the African plate.)

Furthermore, the Somalian and Nubian plates progressively separate from the Arabian plate situated to the north. These plates intersect within Ethiopia’s Afar region, producing a Y-shaped rift system, as indicated by the Geological Society of London.

The genesis of the East African Rift can be traced back approximately 35 million years ago, originating between the Arabian Peninsula and the Horn of Africa in the eastern reaches of the continent. Cynthia Ebinger, a geology chair at Tulane University in New Orleans and a scientific advisor to the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of African Affairs, imparted this information to Live Science. Over time, this rift expanded southward, reaching northern Kenya around 25 million years ago.

The rift manifests as two broadly parallel sets of fractures in Earth’s crust. The eastern rift traverses Ethiopia and Kenya, while the western rift follows an arc from Uganda to Malawi, per the Geological Society of London. The eastern branch presents an arid environment, while the western branch lies adjacent to the border of the Congolese rainforest, as detailed by NASA’s Earth Observatory.

The existence of both the eastern and western rifts, coupled with the identification of offshore regions replete with seismic activity and volcanism, suggests that Africa is gradually parting ways along numerous fault lines, collectively expanding at a rate surpassing 0.25 inch (6.35 millimeters) per year, as conveyed by Ebinger.