Surprisingly, only a small fraction of the over 3,000 mosquito species are truly specialized in biting humans. Most, instead, feed from a variety of sources. However, Aedes and Anopheles mosquitoes are notorious for their preference for human blood and their role as vectors for human diseases. Aedes mosquitoes are linked to Zika and dengue fever, while Anopheles carry the parasites that cause malaria.

Some mosquito species not only show a strong preference for human blood but also appear to “discriminate” between individuals when choosing their meal. While this has long been anecdotal, it’s now backed by scientific research. So, why does this happen? What factors influence a mosquito’s choice of blood meal?

Dispelling Myths: What Doesn’t Attract Mosquitoes (Much)

There are many anecdotal explanations for this phenomenon, but some sound more plausible than others. Some people believe it’s due to blood type, having “beautiful” skin, or certain types of sweat. Even eating foods like garlic, vinegar, or apples are thought to influence mosquito bite rates in one way or another. However, these popular theories often hold little scientific sway when rigorously tested.

Despite the myths, extensive research has been dedicated to understanding mosquito biting preferences, primarily with the hope of manipulating their behavior to control human diseases.

The Real Reasons You’re a Mosquito Magnet

It’s not that one person’s blood tastes “better” to these tiny bloodsuckers. During a TED 2014 conference in Vancouver, Canada, microbiologist Rob Knight explained that bacteria, or microbes, on the skin produce different chemicals, some of which are more appealing to mosquitoes.

All female mosquitoes need to feed on blood to nourish their eggs during reproduction. Some species will only feed on animals, while smaller species target humans. It’s challenging to determine precisely how mosquitoes detect human blood and differentiate between individual scents. We only know that when searching for a meal, they utilize a range of specialized senses that function like moisture and CO2 detectors.

Mosquitoes can identify up to 300 different chemicals that we emit into the air daily. With over 3,000 different mosquito species, each has a predetermined innate preference. For instance, some species are quite aggressive, while others seem gentler. Some mosquito species even choose only our feet as their “dinner” location.

Previous studies indicate that most mosquito species prefer darkness, warm places, or high CO2 concentrations. They are attracted by movement and alcohol vapor when we drink. Some individuals with thinner skin or Type O blood are preferred targets for mosquitoes. And uniquely, they love sweat.

The Power of Skin Bacteria and Genetics

Billions, or approximately that many, bacteria live on the skin, which is a tiny fraction of the total 100 trillion microbes living on and in the human body. However, they play a crucial role in producing body odor. Without these bacteria, human sweat would be odorless.

Crucially, the composition of these different bacteria varies significantly from person to person. Knight explained that while our DNA is 99.9% identical, most people only share about 10% of their skin bacteria in common.

To illustrate how mosquitoes are attracted to specific types of skin bacteria, researchers asked 48 male volunteers to abstain from alcohol, garlic, and spicy foods and to shower for two days. These individuals then wore nylon socks for 24 hours to collect a unique set of skin bacteria. The researchers then used glass beads rubbed on the volunteers’ feet to collect their scent as bait for mosquitoes.

The results showed that 9 of the 48 volunteers were highly attractive to mosquitoes, while the scent of 7 lucky volunteers was completely ignored. The “highly attractive” group had 2.62 times higher concentrations of common skin bacteria; and 3.11 times higher concentrations of other common bacteria compared to the “unattractive” group. The less attractive group had a more diverse range of resident skin bacteria.

Some mosquito species prefer the smell of fresh sweat. Others prefer the aged odors produced by bacteria on the body over time. In short, when you sweat and are not clean, you become a bigger target for mosquitoes than ever before.

The Role of Genes and the Future of Repellents

Researchers suggest that some people might naturally emit scents that act as natural mosquito repellents. However, there are still solutions for those with a natural attractiveness to mosquitoes, such as reducing beer consumption. People who drink beer are highly attractive to these insects, according to researchers. But one thing they cannot change is their genetics.

It sounds illogical, but it is the result of studies confirmed multiple times by scientists: 85% of the reason someone gets bitten more by mosquitoes is related to their genetic traits. The latest research on this was conducted and published in April by scientists from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

They selected 18 pairs of identical (monozygotic) twins and 19 pairs of fraternal (dizygotic) twins for the study. This standardized all conditions for the control groups, leaving only genetics as a variable for mosquito attractiveness.

The results were as expected. James Logan, the entomologist who led the research team, stated, “Identical twins had very similar levels of mosquito attractiveness. However, this was very different in fraternal twins. Therefore, the answer to why someone is attractive or unattractive to mosquitoes comes down to genetics.”

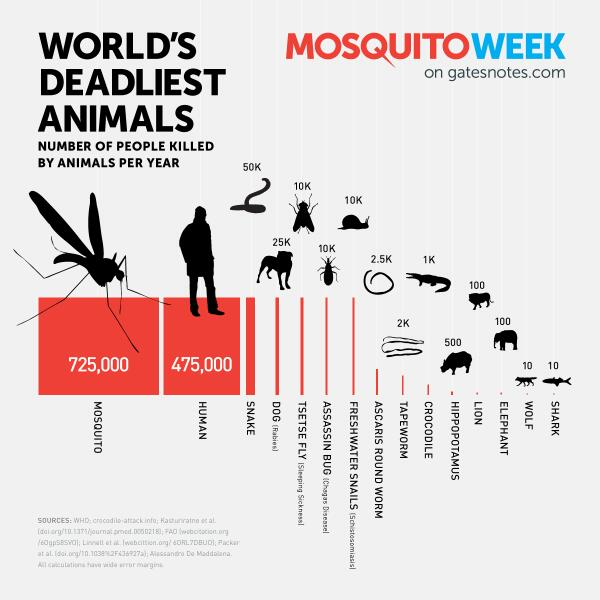

This conclusion will likely steer mosquito prevention research in a different direction. “If we can understand how genes influence this, we can develop new mosquito repellents,” Logan said. This could be the basis for addressing many horrific diseases for which mosquitoes are the leading killers of humans.

The best tool we have today for mosquito prevention is DEET, a compound developed by the military in 1952. However, it is unfortunately listed as a neurotoxin, albeit a mild one. Permethrin, an insecticide used to combat mosquito-borne diseases, is even worse. Recent reports claim it has the potential to cause cancer.

Therefore, research into mosquito preferences for certain individuals is not just to answer your simple question. It will be an opportunity for us to overcome barriers in the fight against mosquito-borne diseases. After more than half a century of using DEET and Permethrin, they have proven to be imperfect solutions. “The more we understand what’s behind mosquito preferences, the better our chances of designing better strategies to protect people,” concluded Richard Pollack, an entomologist and public health expert at Harvard University