Don’t scratch yet! According to researchers, Demodex mites seem to be harmless to the human body, and chances are, anyone reading this probably has them living on their face right now.

The Shocking Truth About Your Skin’s Tiny Tenants

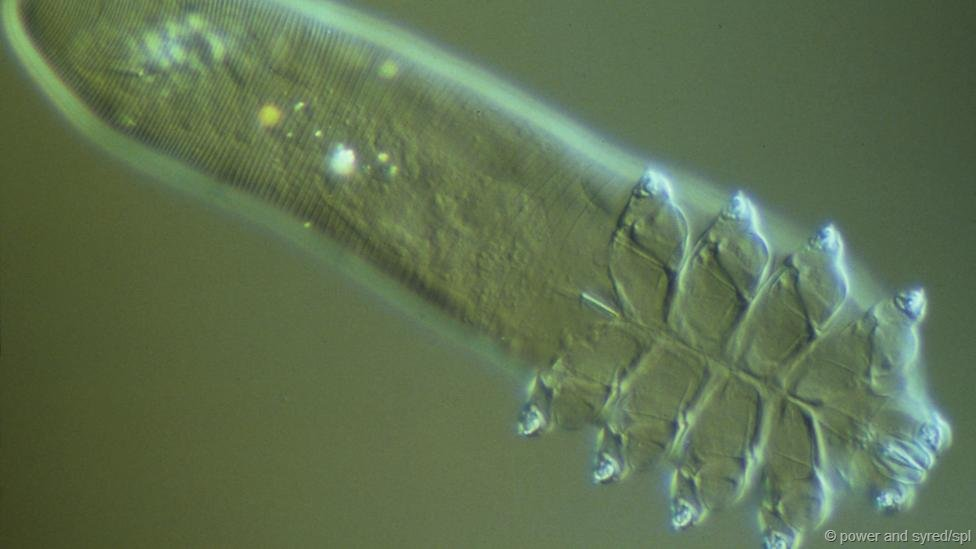

First things first: you cannot see them with the naked eye. This invisibility allows them to live comfortably and freely on everyone’s “front yard” (i.e., your face). However, if you “try hard enough” with the help of a magnifying glass or microscope, you might just catch a glimpse of these worm-like or grub-shaped mites crawling under your skin.

General Description

Demodex mites were first discovered by Gustav Simon, a German dermatologist, in 1842. Nearly 200 years later, scientists are still not entirely sure why these mysterious mites exist and live on mammals. According to Michelle Trautwein, an entomologist at the California Academy of Sciences (USA), Demodex and mammals simply evolved together over time.

“Demodex aren’t just on human skin; they’re on all mammals. They evolved on early mammals and continue to co-exist,” Trautwein told Insider.

Demodex is the name for a type of parasite (also known as a mite). They are among billions of parasites, and Demodex are among the smallest, making them very difficult to see with the naked eye. These parasites prefer to reside in hair follicles and sebaceous glands in areas like the face, nose, forehead, chin, and eyes.

There are two species of mites that “prefer” living on human faces: Demodex folliculorum (D. folliculorum) and D. brevis (collectively called Demodex). Despite their worm-like appearance, they are actually crustaceans, similar to insects or crabs. Their closest relatives are spiders and ticks.

A D. folliculorum mite’s head has eight legs. Its body consists of a head with eight short, chubby legs evenly distributed on two sides, and a body and tail of equal size that extend into a large segment, making them look like worms. However, due to this extreme asymmetry, Demodex mites move very slowly. Under a microscope, Demodex appear to be swimming in “pools” of oil beneath the human skin.

These two Demodex species are primarily distinguished by their living locations. D. folliculorum prefers to reside near the skin’s surface, in pores or hair follicles. D. brevis lives deeper, beneath the epidermis of the skin, inside the sebaceous (oil) glands surrounding human hair follicles.

Compared to other parts of the body, human facial pores are wider and have more sebaceous glands. That’s why Demodex mites prefer to parasitize there more than other areas. However, for some “sensitive” reasons, Demodex are also found around women’s breasts and in the genital area.

Unique Characteristics

Scientists have actually known about Demodex mites for quite some time. In 1842, D. folliculorum was discovered in human earwax in France. However, they were not thoroughly studied until now. It wasn’t until 2014 that researchers at North Carolina State University (USA) began to investigate this species. Among all individuals studied, 14% had detectable mites living on their faces. All the rest showed traces of Demodex DNA after the mites had died!

This leads to the suspicion that every single one of us harbors Demodex mites, if not in large numbers, then certainly in significant quantities on our bodies. Megan Thoemmes, who led the research team, stated: “It’s still a bit difficult to determine the exact number, but a small population of mites can number in the hundreds. A large population can reach thousands.” In other words, there could be a mite swimming under every single one of your eyelash follicles.

Naturally, some individuals will have more mites than others, and vice versa. It’s also possible that on the same person, the left side of the face might have more mites than the right, or vice versa.

However, researchers have not yet answered the question – what do these mites seek on our faces? In fact, we still haven’t clearly identified Demodex’s diet. “Some people suggest they eat the bacteria that normally live on our skin. Others think they eat dead skin cells. Still others believe they consume the oils produced by the sebaceous glands,” Thoemmes added.

Currently, Thoemmes and her colleagues are analyzing microbial samples from Demodex guts. These organisms might help us understand what these mites consume on our faces.

The reproduction of these mites is also an interesting issue. Although Demodex are currently considered harmless, many people undoubtedly want to eliminate them. Thus, understanding how Demodex reproduce is crucial. Considering other mite species, their reproduction methods are highly diverse, ranging from “traditional” mating to incest and cannibalism. But Demodex seem much “gentler.” “There have been no reports of them eating other mites. It seems they only leave their ‘nests’ at night to find mates and return afterward,” Thoemmes commented.

However, the research team does have clear information about Demodex egg-laying. The entire process has been captured on video (not provided here). Specifically, female Demodex lay their eggs directly within the hair follicle where they reside. Demodex do not lay many eggs; almost always just one egg per laying.

“Their eggs are truly large, about 1/3 to 1/2 the size of their body, which would require them to replenish their bodies significantly. Their eggs are so large that they can almost only lay one egg at a time. And I cannot imagine if any more eggs could fit into their bodies with such a size,” Thoemmes remarked.

But these mites have one very strange characteristic – they have no anus. So how do they excrete waste? Of course, they still need to “release” it, but in a very dramatic way – Demodex mites “explode” upon death. It seems this creature “stores” waste throughout its life, which is why they have long, worm-like bodies and tails. And after the metabolic processes in their bodies cease, the Demodex body dries up, and all its waste is scattered around. The phrase “explode” might be an exaggeration, but clearly, upon death, this species’ feces are spread across your face.

Beneficial or Harmful?

Facial mites (Demodex folliculorum) do not have an anus. They also do not excrete through their mouths like some other organisms. All waste produced after eating skin cells and sebum on the human face is accumulated in their guts. With this peculiar digestive system, facial mites live for a maximum of 16 days. After they die and decompose, the waste remains on the human face, combining with bacteria that can cause skin inflammation (rosacea).

There have been studies suggesting a relationship between Demodex mites and chronic rosacea. Specifically, some people initially experience facial redness, which then becomes permanent, with darker red nodules appearing and increased sensitivity to changes in environmental temperature. These studies found that individuals with this condition often have significantly more Demodex mites than average people. For example, instead of just 1-2 mites per square centimeter, they might have 10-20.

However, that does not mean they are the causative agents of rosacea. The number of Demodex mites could merely be a consequence of the disease. Kevin Kavanagh, from Maynooth University (Ireland), states: “The mites are associated with rosacea, but they are not the cause.” In his 2012 research, Kavanagh concluded that the increase in Demodex “population” stems from changes in human skin.

Specifically, our skin changes over time, as do living conditions and environment. These factors cause the sebaceous glands beneath our skin to secrete more oily substances to keep our skin moist. It is very likely that Demodex mites feed on these oils, so if more oil is secreted, they have more food. As a result, the Demodex “population” skyrockets.

Kavanagh describes: “This phenomenon leads to inflammation on our faces because too many mites are produced. When these mites die, they release the substances within their bodies. These substances contain many bacteria and toxins that lead to itching and inflammation.”

However, Demodex dying is probably more related to our immune system. Thoemmes notes that in patients with weakened immune systems, such as those with AIDS or cancer, the number of Demodex mites becomes quite significant. “I think the mites ‘explode’ because your body has an immune reaction to something on them. Rosacea is just one such reaction.” When the immune system is weakened, such reactions are fewer, allowing Demodex to proliferate rapidly.

In reality, the relationship between us and Demodex mites is still not fully understood. Whether it’s parasitism or commensalism remains an unanswered question. Although Demodex are linked to rosacea, not everyone develops the condition, and people with AIDS or cancer are also susceptible to other diseases due to weakened immune systems. What’s notable is that despite being present on most people, we generally don’t feel any “discomfort” from them.

And if the hypothesis that Demodex mites also eat bacteria living on the skin or dead cells (in addition to their “menu” of fats) is true, then they are clearly beneficial to the human body. Imagine sanitation workers diligently cleaning your office; Demodex mites could very well be performing that role.

They “Love” Humans

But surely many of you still want to get rid of these eight-legged creatures from the pores on your bodies? The answer is almost… impossible!

Although there are some methods to eliminate Demodex mites, they always reappear within about 6 weeks. And the source of infection, of course, comes from objects around us and the people we live with. “We get them from people we have contact with. We get them from blankets, pillows, towels. There’s clear evidence that we ‘exchange’ them back and forth between individuals,” Kavanagh stated.

And Demodex mites “love” human faces. Regardless of how they’re transmitted, they always find a way to crawl onto our faces. The presence of these mites around women’s breasts could also be a way for them to transmit to newborns when mothers breastfeed. Sexual intercourse between humans is also a good pathway for Demodex transmission.

Especially as we age, the number of Demodex mites increases. Thoemmes’ research shows that Demodex activity in people over 18 is significantly higher than in adolescents. This could be due to the activity of sebaceous glands or changes in facial skin with age, stimulating their growth.

But above all, where do these mites come from? Of course, they don’t spontaneously generate on our faces but are transmitted from others. So, what’s their origin?

Origin

There is still too little information for a definitive answer, but it seems that Demodex has accompanied human evolution. Thoemmes speculates that they may have been present with humans “since we evolved from our Hominidae ancestors.” This means Demodex mites have “coexisted” with humanity for at least 20,000 years.

But there’s also a possibility that humans contracted the D. brevis species from a similar species living on dogs. When humanity domesticated wild dogs, especially wolves, an exchange likely occurred. “Our ancestors lived closely with them, hunting and foraging, and were infected from there,” Thoemmes commented.

However, either way, the relationship between humans and Demodex is ancient. According to Thoemmes, Demodex can help understand human migration patterns over thousands of years. By observing the DNA samples of the mites, Thoemmes found that mite groups collected from Chinese communities differed significantly from those in North and South American communities. This detail suggests that research on Demodex mites can provide more information about human history.

“We can infer relationships within human communities… Relationships we never thought of before,” Thoemmes commented. For example, the colonization process of Central and South America, and which human groups played a primary role. “There are many different hypotheses about which human communities colonized Brazil and interbred with indigenous populations.”

Conclusion

And there’s still much more to research about Demodex, such as how they transformed when they transmitted to humans, or how humans have changed since acquiring them. Of course, not every question or hypothesis can be proven correct. But ultimately, Demodex is just one of dozens of other parasitic species on the human body, such as ticks, fleas, bacteria, worms, etc. This highlights another lesson about the human body. We are not simply “us” – we are a moving organism, a part of the human community, and also a vibrant ecosystem with hundreds of species sharing that very body.